Brickworks of Stoke-on-Trent and district

|

|

|

|

Brickworks of Stoke-on-Trent and district |

|

- click here for

photos of Wheatly Brick Works -

- click here for 1930 advertising booklet for Wheatly -

Wheatly Brick & Tile Co

Trent Vale, Newcastle

(note: The name is spelt 'Wheatly' and not 'Wheatley')

An article by Gladys Dinnacombe

and used by her kind permission,

Gladys was born in May Bank and related to brickmakers at the Wheatly Brick

Works

This article first appeared in The Open University Geological Society Journal

Spring 2002

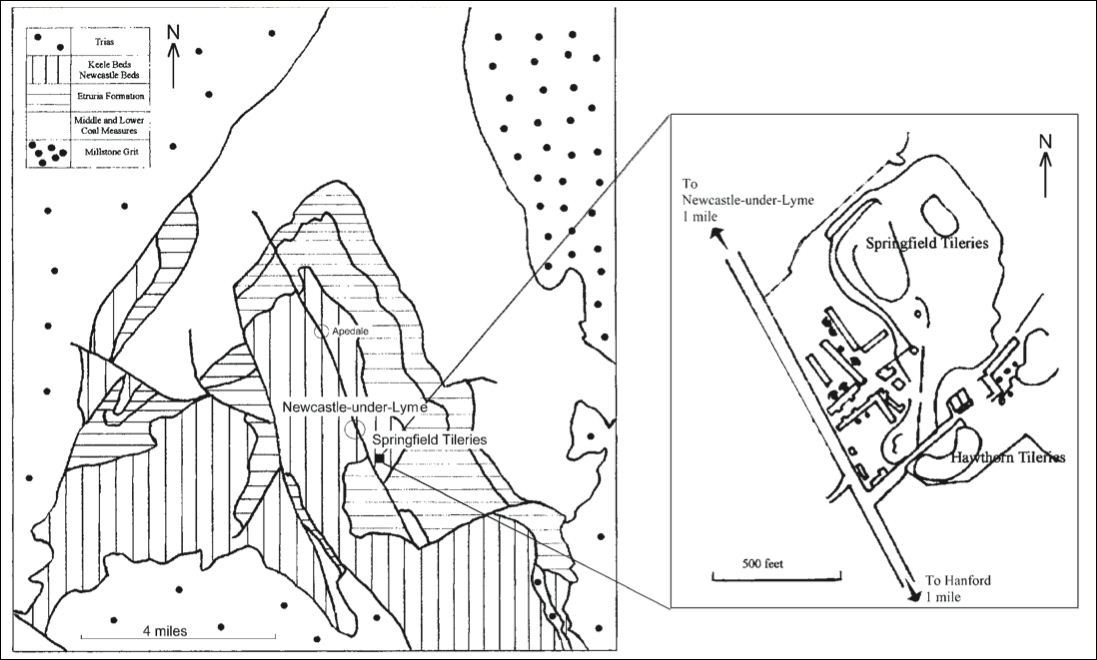

Figure 1. General geology map of the area and the extent of the workings in 1899

Springfield was the Wheatly Brick & Tile Works

|

Researching my family history has been an interesting hobby and as I got further back in time to the 1850's, I discovered my ancestors had been brickmakers in Newcastle-under-Lyme, North Staffordshire (Figure 1). In the 1851 Census, my great-great-grandfather lived with his family, next door to his brother and his family. All the members of the family who were old enough to work, and that included the female members, worked in the brickworks as brickmakers. Looking at old maps of the area led me to believe that they worked in Springfield Tileries, the local brick pit known (during my lifetime) as Wheatly's Brick and Tile Works. (Figure 2).

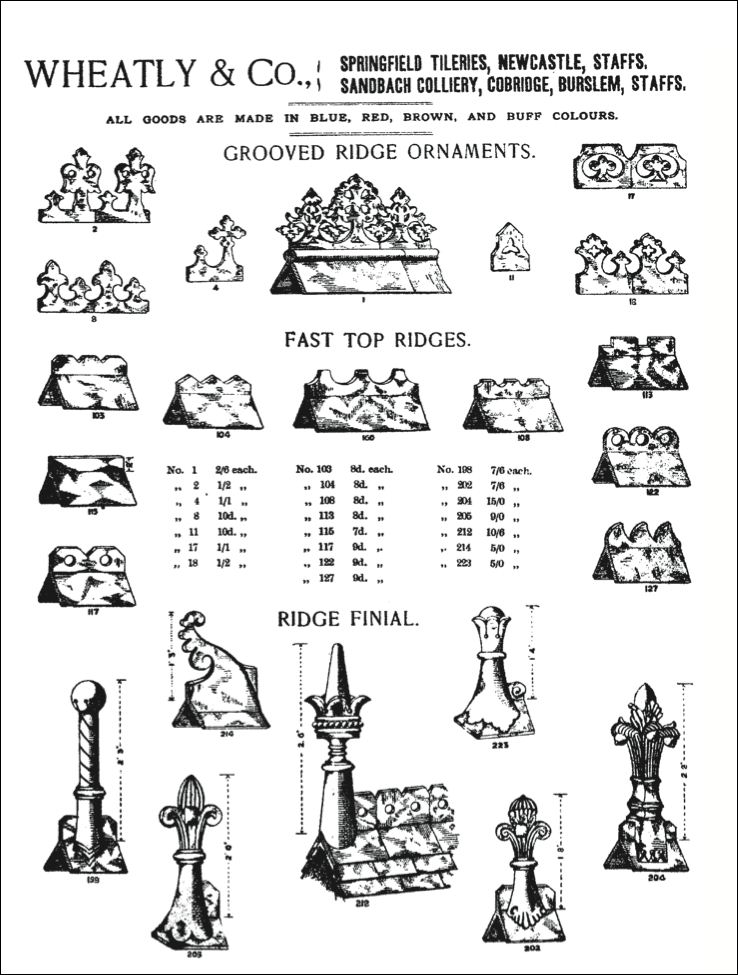

My memories during the late 1950's and early 1960's are that the buildings of this company could still be seen although I do not know if the pit was still being worked at that time. Further research led to the study of old maps and a small advertising booklet dating from 1930 (Platt 1995) was discovered. This booklet showed small drawings of the tiles produced and how they were made. This will be discussed later.

In 1850, Dobson (see Celoria 1971) wrote a treatise on brick making. He gave some interesting information about the uses of bricks besides buildings: ‘a common turnpike road bridge over a railway requires for its construction, in round numbers, 300,000 bricks; and the lining of a railway tunnel of ordinary dimensions consumes about 8000 for every yard in length, or in round numbers, about 14,000,000 per mile’. At this time, the brick industry was well established in this area, and the beds of the Coal Measures have now been worked for brick clay, for around two centuries.

BGS divide the Etruria Formation into three parts, Lower, Middle and Upper (Figure 3).

So what did my ancestors do as brickmakers? Dobson (1850) (see Celoria 1971), in his treatise on the manufacture of bricks and tiles, gives us plenty of information.

The census also gave his place of birth as Wickham in Huntingdon, so he was not a local man. The booklet tells us that in clay pits at Springfields, there were as many as twenty different seams, free from lime, which enabled a wide range of mixtures to be obtained without resorting to the use of artificial colouring matter. By this time, there had been some changes in the clay making process.

The mixing process itself intrigued me. Measuring was done by the barrow load; barrow loads of each of the required clays being tipped into trucks and then properly mixed. This mixture was then taken to the grinding sheds and ground ready for the next process. At the time of the printing of the booklet, the grinding was done via a series of rollers from an automatic feeder, the only one of its kind in Staffordshire at that time. After grinding, the clay mixture was soaked with water to induce plasticity and allowed to lie in stacks called rucks. The clay lay there for several weeks or even longer. This process, called souring, could be affected by the weather unless roofs were made over the rucks. When ready, the clay was then taken to be pugged followed by another short rest before being ready for moulding. The booklet shows 14 different types of bricks and tiles.

In this area the kilns were circular, domed over at the top and called cupolas. Fire holes were openings left in the wall, and these were protected from the wind by a wall built around the kiln (Figure 5). Up to 8000 bricks could be fired in one cupola. Dobson also details the total cost of manufacture and the selling price (Table 2). At this time, 1850, it seemed that being a brick-maker was only a part-time job, in that during the winter there would be no work. Dobson stated that, by being more systematic and by using buildings designed specifically for the purpose, brick making could become an all year round occupation. No wonder that families working in the brick industry during the early 1800’s were poor!

Before being fired, as techniques improved, the bricks and tiles were fettled or dressed, so that any small bits adhering from the moulding process that were not required were removed. Horsing, another technique, obtained a camber on the tiles so that they were more efficient in use. By 1930, the time when their booklet was published, some tiles were being made by machine but Wheatly and Co. were proud of themselves as they still produced quality hand made tiles. The final page of this booklet shows a series of small woodcut style pictures showing different people at work (Figure 6). There is also a copy of a photo of some of the staff employed at Springfield. Despite close scrutiny I have not yet found any of my ancestors.

Today, only one main manufacturer of bricks and tiles remains in this area and their main factory is across the road from where my mother lives. This brickworks has the longest kiln in the country and produces many kinds of bricks. Their website offers a great deal of literature about bricks and their use. So how has brick-making changed over the years? One important feature today is the consideration of the impact on the environment caused by the manufacture of bricks. This means that quarries are restored after being worked out and also chimney emissions are regulated. The bricks themselves are all moulded by machine, many different types being produced. These include perforated, frogged (bricks with depressions in one or more surfaces) and engineering bricks. There is also a range of special shaped bricks which includes angle and cant, arch, bonding, bullnose, capping and coping, cill, plinth, soldier and spiral. I wonder what my ancestors would have thought of brickmaking now! From Genealogy to Geology OUGS Journal 23(1) References

Author

- click here for photos of Wheatly Brick Works -

|

Figure 4. Illustrations from the 1893 Catalogue (Sears

1893)

- click here for

photos of Wheatly Brick Works -

- click here for 1930 advertising booklet for Wheatly -

Questions, comments, contributions: Steve Birks

|

Page created 1 December 2014 |