|

Trent Vale - probably the

most important place in Stoke-on-Trent

Most locations in Stoke on Trent carry a road sign telling you where you are, but Trent Vale doesn’t. And yet it ought to for, historically, it is probably the most important place in Stoke on Trent.

Mark Bailey, known as the Trent Vale Poet, equates with his home town as well as anyone. He has written plenty of poetry about Trent Vale, and yet with a note of poignant resolution he says, “Once I was a songwriter without a singing voice, now there is just me and my po-et-ry. I go out with the band and my poems are pretty well respected. They stand alone.”

Like most Trent Valeites Mark knows very little about its ancient history, but here in Trent Vale the earth moves for him. “Before I arrived the only thing I knew about Trent Vale were that it had had a lot of earth tremors in the 1970’s. And that’s about it really – mini-earthquakes. We moved here in 1981 and I’ve raised my family here – kids at the local schools etcetera. It’s a cool place.”

From its boundary with the City General Hospital the geography of Trent Vale is shaped like a triangle with Springfields and Penkhull in the north falling to the Trent Valley through Boothen and Oakhill. It’s a mishmash of old hamlets with a lot of tree-lined streets, some edged with Sutton Trust Houses that improbably have seen three generations of families raised in their tiny rooms.

The Trent Vale poet uses allegorical language and describes the walls of houses as being sick with measles; the floors are suffering with mumps and the ceilings are struggling with lumbago. Mark speaks a sort of municipal ghetto lingo – a sanitised rap about yobs ‘hurling concrete lumps at local chumps beneath ever-grey skies.’

Through his cynical trademark however I get the impression Mark really likes and respects his hometown.

“People refer to me as Trent Vale,” he says proudly; “No, not the place, me! They think that’s my name! Very Hollywood isn’t it?”

Black humour and comic poems – “‘If you don’t laugh you’ll cry’ type of stuff,” he says.

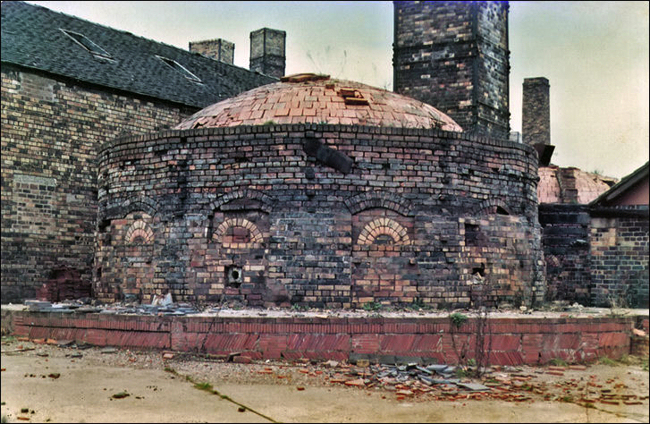

Brick Kilns at

Wheatly & Co Ltd., Springfield Tileries, Trent Vale

demolished c.1982

photo

courtesy of 'Tarboat -Flickr'

The Michelin Tyre Company arrived in 1927 and occupied

80 acres of land between London Road and Campbell Road

Trent Vale is a place that was once very important in industrial terms. Brick and tiles that were central to Stoke-on-Trent’s building industry were made here for many years. The Michelin Tyre Company arrived in 1927 and occupied 80 acres of land between London Road and Campbell Road. And millions of baker’s dozens are still cooked weekly at local bakeries, though not as many as fifty years ago.

Overlooking the recently flattened Michelin factory Mark and I meet up with two of Stoke-on-Trent’s principal academic historians, Bill Klemperer, an inspector of ancient monuments for English Heritage, and Debbie Ford, Collections Officer for Local History at the Potteries Museum and Art Gallery. Why is Trent Vale so important I ask? Bill began a narrative.

“In the late 1920s a local archaeologist and school teacher, Thomas Pape, was walking around Trent Vale and quite literally picked up a comprehensive load of Roman Samian pottery made from local clays. In the 1950s a Stoke-on-Trent museum curator, Arnold Mountford, decided that the evidence of Roman occupation was so overwhelming that he made some trial digs.

In addition to the pottery some Roman coins were unearthed among stratified layers that were shown to be levels of buildings – pinch holes they are called – where posts had been set down for vertical constructions. There was a clay-lined ditch to enable water to flow through various parts of manufacturing areas. And there was confirmation of the establishment of workshops and this is where they found Stoke-on-Trent famous earliest pottery kiln.”

Pottery found in Trent

Vale Roman potter's kiln

photo: Stoke-on-Trent museum

Debbie points out that, “In the 1950s archaeologists excavated in a different way than they do now – not in an open plane – they excavated small areas in trenches or boxes. On this site they found wattle and clay daub constructions with clay floors. A full 1956 report said there was a profusion of pottery shards and all this indicated that there had been at least one potter’s workshop on the site. Further trial bores unearthed pottery, coins, buttons, wine jars and an amphora which is a very special vessel for carrying olive oil.”

Debbie describes the kiln as a simple up-draft oven which means the air enters the base to a focal area where the potter lays the ware. The air passes through and up out of a small mound or chimney at the top. “It doesn’t have to be a chimney,” she says, “it could be level with the ground. These were the ovens that contained the stacked wares. The archaeologists also found Claudius-impressed coins in a ditch nearby.”

The invasion of Britain under Claudius in AD43 is dated fairly accurately, but the interesting fact is the site at Trent Vale can be positively dated just two years later. Trent Vale must have been an important staging post where soldiers garrisoned.

“It is more than likely that this site was a military depot,” says Debbie, “with supporting services including potters. These were associated military personnel, accompanying legionaries across the country carrying back packs full of stuff. The timing of course is crucial. Trent Vale at this period would have been a frontier zone and remained so for some time later.”

Is this proof that for a significant interlude Trent Vale was an important Roman settlement?

“The kiln can be dated no later than AD60. Taken the other proof it possibly indicates that the settlement was here for at least 25 years. What is fascinating is that it is so early in the Roman occupation of Britain. Material was continental – Samian ware would have been made in Gaul then under Roman occupation,” explains Debbie.

Bill says, “The Romans quickly realised that this area held here was an abundance of coal and clay. Trent Vale is the site of the first dated pottery production in the area. It sets the template for the all later Potteries. The ancient art of potting has changed very little and in the early 1700s kilns and pottery production must have been very similar to Roman activity.”

Unfortunately the 1950s digs were limited in their scope. Enhanced excavations were later undertaken at the fortress of Chesterton along the Roman road that passed alongside and across the Trent Valley. Chesterton was one of five known major Roman centres in Staffordshire. These centres represented military movement through the county on the route to the principal garrison at Chester.

Before the Romans arrived Debbie considers that Trent Vale was more than likely an Iron Age settlement. “As everyone knows you might get an invasion but the local population doesn’t change overnight – people don’t suddenly become Roman or Romanised. Of course people would have adapted to Roman ways but by the end of the occupation 400 years later many would still be living in their own pre-Roman traditional ways.”

The iconic kiln at Trent Vale was one of the first Roman influences in this area and the locals would have been amazed by it. It may not have been operating very long – perhaps while they were moving on to better locations up and down their roads. But, as Bill says, “We know from the last firing that the kiln dome collapsed on top of the pots. When it was excavated the entire contents of the last firing were revealed. These were a collection of large rusticated pots – deliberately roughened on the outside by the addition of grit to make them easier to handle.”

Debbie says, “There is one exceptional face pot – a red unglazed vessel with features picked out in relief – it is the image that is used to promote the Potteries Museums on our leaflets.”

There is no evidence of any other Roman kilns in this area although there was a massive site at Mancetta outside the south east of Staffordshire where a huge pottery manufactory was established. It was kept going for years and obviously supplied traffic passing along Watling Street. And sadly, by comparison, we don’t know all that much about the Trent Vale site even from the excavation plans. The landscape has changed dramatically. The tile and brick works have gone. A huge marl pit was filled in long ago. The limitations of the 1950s excavations are inconclusive. Who knows what might have been found or missed had industry not forced the hand of heritage? Everything has been disturbed by the pillage of industry, much of it buried and reburied under the Michelin factory. Incalculable damage has been caused by modern occupation therefore we will never know just how important the settlement at Trent Vale really was.

The four of us leave the land to its changing history as Mark begins to recite his epic Trent Vale poem over the Michelin valley and across the Millennia back to Roman times:

‘It never rains in Trent Vale the people won’t allow it,

They shake their oatcakes at the sky daring God to try it.

A few spits and spots and nothing more, the sun is always shining.

It’s the Mediterranean of the north, washing lines and ironing.

Men parade in flip-flops, women walk around in shorts;

Children, lightly grilled, sip alcopops through straws.

No it never rains in Trent Vale the people won’t allow it,

They shake their oatcakes at the sky daring God to try it.’

Across the Potteries it’s raining but today in Trent Vale the sun really is shining – honest.

Fred Hughes

|

![]()

![]()

![]()