![]()

|

|

|

|

|

Stoke-on-Trent - Potworks of the week |

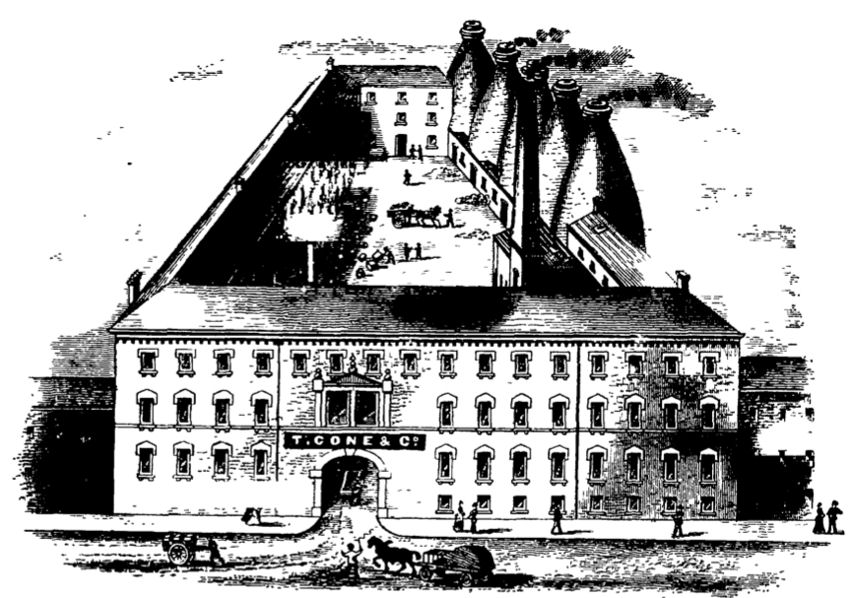

Advert of the Week

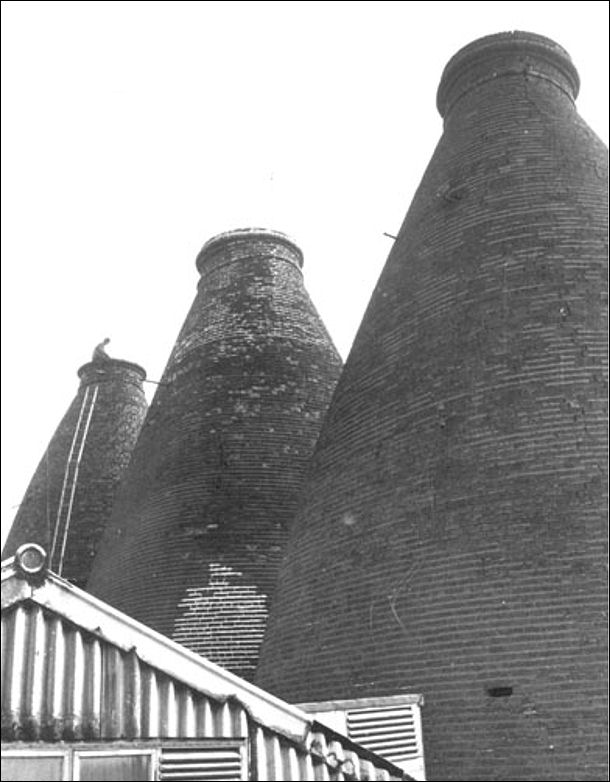

Photo of the Week

Alma Works Works, High Street, Longton

The works appear to have been established in 1856 by a previous pottery factory owner.

Occupied at some time by Copestake & Allen

1884-88 occupied by Middleton & Hudson

Originally (c.1892) as T Cone & Co - in partneship with Lewis Bentley

Then as Thomas Cone Ltd. (1893 - c.1920)

About 1920 the business was acquired by Thomas C Wild & Sons and was renamed Thomas Cone (Longton) Ltd.

- click for more on Thomas Cone -

Thomas Cone, Alma Works in

1907

High Street (now Uttoxeter Road), Longton

Taken at the Alma Works,

Uttoxeter Road, Longton, Stoke-on-Trent - c.1955

Pottery factory exterior including bottle

ovens, which are in the process of being demolished.

Due to the proximity of other buildings the first of the three bottle

ovens is being dismantled brick by brick.

Based next door to the Alma works, Shenton's

was a cratemaking and rustic furniture

making company - they purchased the site to extend their own factory.

|

Firing the biscuit bottle oven

at the The old biscuit bottle ovens were the hot throbbing heart of our pottery factory. They were mother figures to those who worked on this or any other pot bank. Big, imposing matrons in full dresses of brown bombazine, their ample wombs weekly brought forth the product of our labour. They followed a 14 day cycle: six days to fill, three days to fire, three days to soak and cool, a day to empty, and a day to repair the internal-brickwork, mainly around the hottest parts (the gluts and the bags). Every clay piece made on the factory had to be fired in one of our two biscuit ovens. Absolutely everything depended on the skills of the fireman and his mate.

Thomas Cone Ltd was old and run down. It was unclear whether I was sent there to test what I had learnt or to teach me a lesson. Our fireman was a red eyed, bloody-minded, unshaven, uncouth old drunk who could fire ovens as perfectly as the baker. On the night in question he lay down on 20 tons of best cobbles, freshly delivered from Florence Colliery, and died. Everything was ready for "kinding off." Dennis, the fireman's mate, had prepared each of the 12 firemouths with four hundredweight of coals topped off with a packet of firelighters and now stood, leaning on his shovel, awaiting orders. It seemed that life's dirty tricks department couldn't wait to expose my lack of practical experience. Firing that 100 year old bottle oven was a lasting lesson to me. For all my book learning I still had enough gumption to realise that bluffing was useless but that scattered through the workpeople around me there was a wealth of practical knowledge in small packets, willingly given if sought.

The first 36 hours were quite straightforward. Black smoke poured from our biscuit bottle oven and down Uttoxeter Road into Longton as the clayware slowly warmed and dried through the "watersmoke" period. Dennis was quite happy slowly feeding the smoky fires and catnapping on the coal. By the middle of the second day the kiln was black hot at about 800 °C. It was time to open the dampers and send the draught roaring through the fires, down under the floor, up the flues among the wares, and out into the filthy sky that daily deposited one ton of grit per square mile of Stoke on Trent.

Flourishes and mumbo jumbo At six in the evening Dennis said to me, "You'll take over from me at ten tonight, then." This was the first time that I fully understood what a fireman was paid to do. Tradition, custom, and practice demanded that the important final 24 hours be done by the fireman himself, with all the flourishes and mumbo jumbo that his exalted position warranted. Mine was a lonely responsibility, and it was quite obvious that it was to be a recurrent event. The only hope of getting a replacement for the late fireman would lie in poaching one from another factory, unless one could be conjured forth. "Dennis," I said, "It's time you saw an oven right through." I believe to this day that he had been waiting for this, and he certainly had a better idea of how to conduct the closing stages of firing than had been credited to him. Through that-long night I explained to him the theory of balancing the four quarters of the bottle oven so that the heat increased evenly throughout. He had never used the gauge for measuring Bullers' rings and it was necessary to explain the concept of the well fired pot as a product of time and temperature represented in these shrinking rings. We discussed the inevitable variations in temperature throughout the bottle oven and how one placed various types of pot so as to take best advantage of this (or, at least, to minimise this disadvantage). We agreed, as the dirty grey dawn appeared, that tunnel ovens would be a great improvement. Later in life I found sitting up with a biscuit oven to be similar to being the all night casualty officer in Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. It was boring and exciting by turns; too hot or too cold; the atmosphere depressing or evocative, according to your state of mind. The hood and hovel were stark, blackened brick, lit only by the orange glow of 12 hungry firemouths. A cold moaning draught swept round the restricted space between the hood of the bottle oven and the circular beehive of the kiln itself, pulled by the throbbing, fiery furnace within. This monster, now that its fires were clear, ate coal at a prodigious rate, but we didn't dare fill a firemouth full for fear of drawing the balance of heat unevenly towards it. We sweated in front of the fires, but crept shivering back within seconds of stepping into the night air. We frowned and fumbled with the fireman's long trial rod, trying to lift Bullers' rings cleanly from the outermost saggers through a peephole, wrapping wet towels around our forearms against the yellow cone of heat blowing out of the small aperture. We worried and waited for measurements, exactly as, in later years, I would await the full dilatation of the cervix in the labour suite at Simpson's. The same responsibility lay with me at that moment, tempered by the same excitement of assisting in the final act of creation.

At eight we shut the dampers and closed the firedoors on each of the 12 firemouths. Dennis went home to bed while I settled into another busy day on the potbank. By six in the evening the last Seger cones had drooped, finally admitting that they had had enough heat. At eight the following morning I gingerly removed the first two bricks from the clammings, the temporary wall across the entrance to the bottle oven. A cold wind whistled into the hot kiln, causing a thousand small, sharp pingings to take up a thousand variable rhythms. To their staccato notes Dennis added a duller slower bass as he "punched' the oven, clearing the clinker from the firebars with a heavy steel rod that resembled the tillerpost of a trawler. By now the pottery inside the oven would be too cool for the fly ash to cling and stain. "Never mind the credit; take the profit" We pinned a cardboard notice to the factory gates: "Biscuit oven emtying [sic] on Thursday." One of the wittier graffiti artists corrected this, adding, "The P is silent, as in bath." At seven thirty on a cold, foggy morning our gang of casual labourers materialised.

Seven years after entering the pottery industry I realised that the senior jobs in our business were passing to members of one family and that this process would continue until the cuckoos had displaced my father, my brother, and me. The difficult trading times that followed the Suez crisis destroyed my father's determination to risk his capital on an independent venture and nearly destroyed my own self confidence. Success in industry comes easily when your father is a senior director of the firm, but it is not clean won and lays no foundations. For the sake of my self esteem I needed to succeed in something desperately difficult. Medicine offered the most daunting challenge that I could imagine, but beyond the struggle lay the greatest prize that life could offer-independence. Department of Anaesthetics, BMJ VOLUME 297 24-31 DECEMBER 1988 |

mark

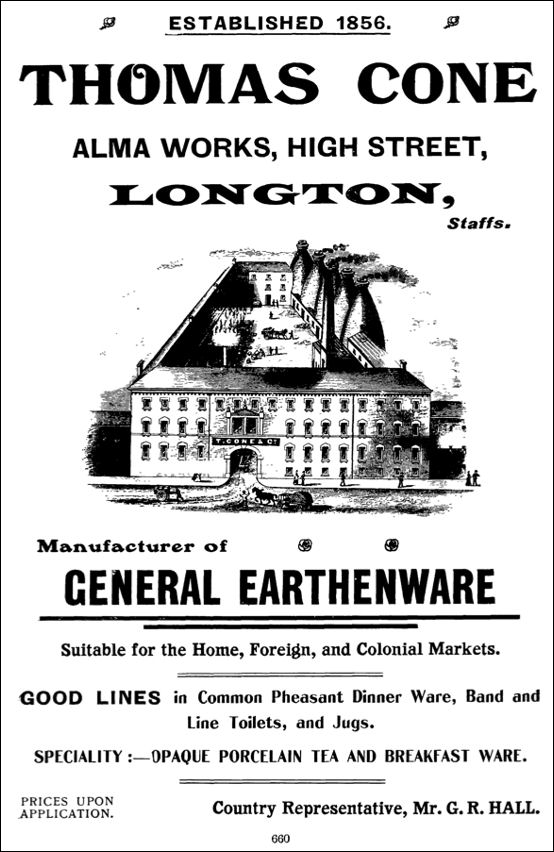

for Thomas Cone

'PHEASANT' is the pattern name

Thomas Cone

Alma Works, High Street, Longton

Manufacturer of General Earthenware

advert from.....

1907 Staffordshire Sentinel 'Business Reference Guide to The

Potteries, Newcastle & District'

- click for more on Thomas Cone -