![]()

|

|

|

|

|

Stoke-on-Trent - Potworks of the week |

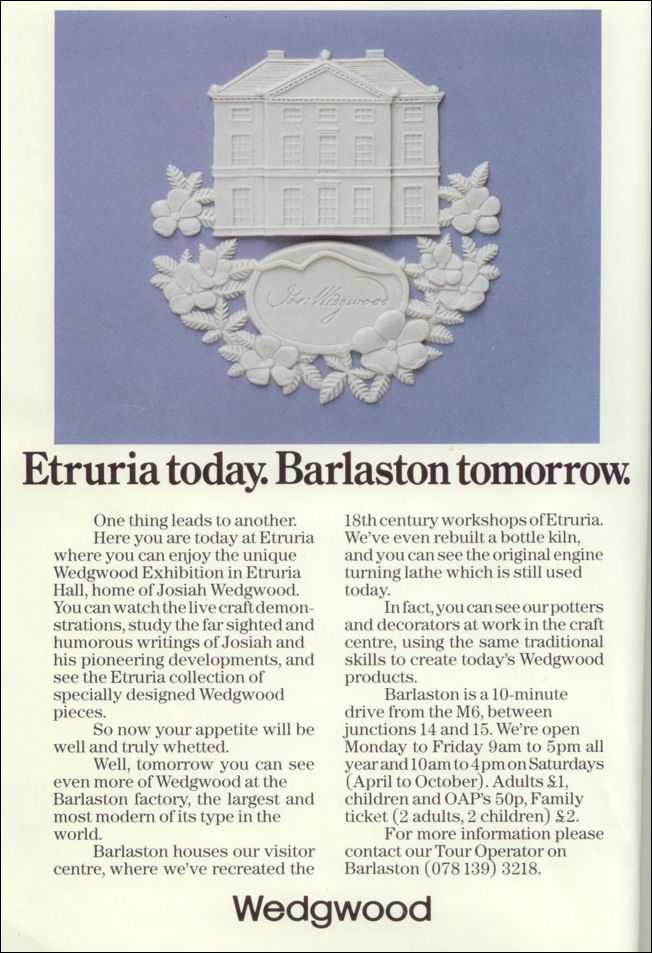

Wedgwood - Etruria today. Barlaston tomorrow.

|

|

Wedgwood - Etruria today.

Barlaston tomorrow.

Wedgwood advert in the 1986 National Garden Festival Stoke brochure

the following photographs of Wedgwood's Etruria Works are from the 1986 NGF Stoke brochure....

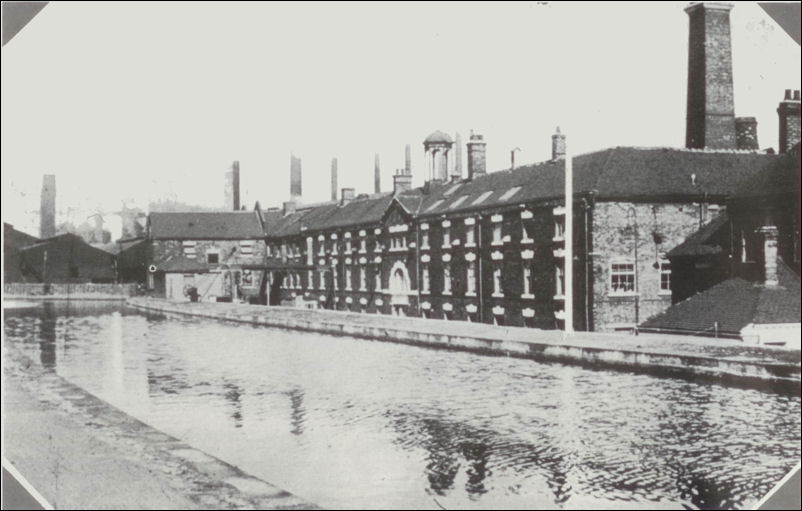

Etruria village with

the Etruria works and in the top left corner Wedgwood's home - Etruria Hall

this was the heart of the Wedgwood pottery business for over a

century

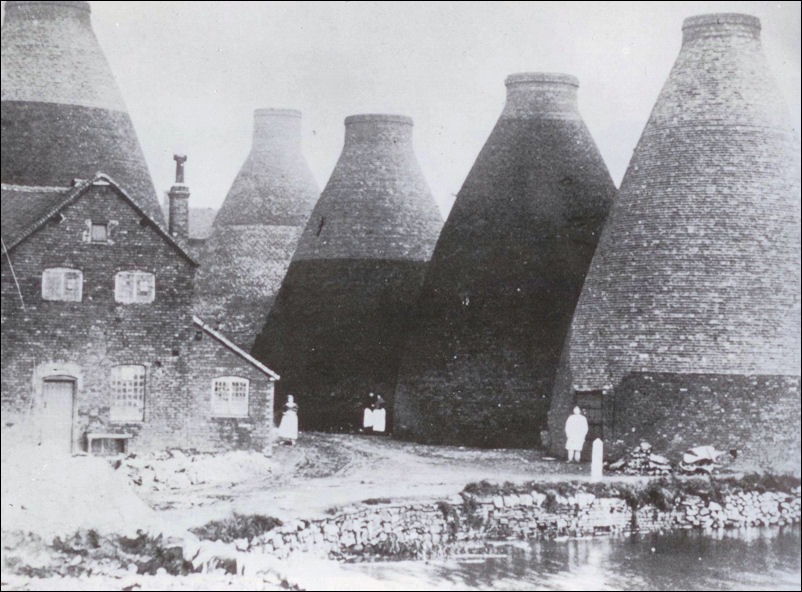

The dominant bottle ovens,

seen here at Etruria, but also found throughout the Potteries

The close proximity of the

canal was essential for the efficient movement of bulky raw materials and

goods

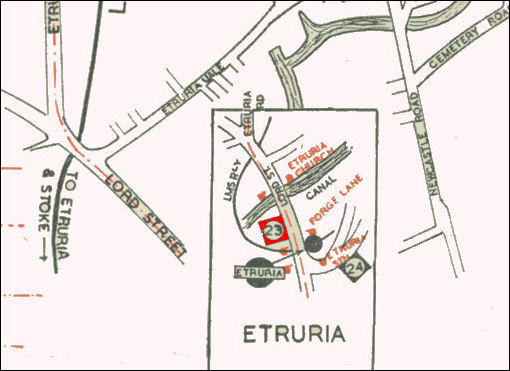

1947 map showing the pottery

works in Etruria

|

| from:

The Factory in a

Garden

The initial problem was simply one of space. Since Josiah I had moved his works into what would now be termed a 'green field site', all the open countryside in Etruria had been built over. When he first encountered the valley in 1759, it seemed to possess every advantage. 'I saw the field was spacious', he recalled, 'and the soil so good as to promise ample recompense to anyone who should labour diligently in its cultivation.'

But inevitably, the conditions which attracted Josiah in the first place —ease of access to the Trent and Mersey Canal, which later would be joined by the London to Manchester railway line, proximity to good mineral reserves, and the availability of plenty of skilled labour in the surrounding Six Towns, proved equally attractive to other processes in the industrialisation of the region. Mines were sunk to extract the coal which ran under the estate, and, of equal importance, an extremely successful steel mill was founded immediately next door to the factory. Nearby there were also a large gas works and long-established bone and flint mills. A spectator looking over the valley from Hanley or Basford would now see nothing but factories and pit heads, with occasional patches of waste ground and clusters of houses. There was no longer any possibility of pushing back the walls of the Etruria premises, and, as a survey carried out by Tom Wedgwood in 1935 confirmed, there were two overriding obstacles to any attempt to clear the site and build a compact new factory.

The first of these was pollution: The notional spectator would in fact have been very lucky if he had been able to see right across the valley at all. Smoke was an old problem, to which the factory's bottle ovens made their own contribution. The Wedgwood family itself had abandoned Etruria Hall, which overlooked the works, back in the 1840s because of the increasingly dirty atmosphere. Most of the processes in the valley were coal-fired, with little effective control over emissions from the boiler chimneys. The railway engines working up Etruria bank alongside the factory wall added to the smoke blowing over the works when the wind was in the wrong direction. To an extent, managers and workers were inured to such conditions. Everyone expected for instance, that if it snowed, the white would have turned black by the following morning. Such was nature's way.

Difficulties which were inevitable in elderly buildings and drains were greatly exacerbated by mining operations taking place near the works. Claude Walker describes the problems which faced him as the factory maintenance man:

The whole site had sunk several feet beneath the level of the Trent and Mersey Canal it had once stood above. Not only the front of the factory but its extensive cellars were filled with water whenever it rained, although in these damp conditions it was still possible to use some of them to store clay and unfired ware. The expensive, newly installed tunnel ovens became extremely difficult to use as their tracks sagged and buckled. The trolleys were derailed and wedged against the walls, and when they were manhandled back onto the tracks again, they tended to run down the slope and jam the doors at the end of the tunnel. 'It needed a very clever fireman to decide how to manipulate them.'

The conclusion reached by the meeting was that: The directors considered the matter a serious one and agreed that the question of a new plant and a new site might have to be considered as a practical possibility in the relatively near future. In these circumstances, it was decided that any extensions to buildings and plant which were not absolutely necessary nor likely to pay for themselves in two years should not be undertaken. The next step to be taken was the selection of the position of the new factory. Given the patchwork development of the Potteries conurbation, there were a variety of possible locations between or adjacent to the townships.

It was a leap into the future which would retain links with the past. Barlaston had been associated with the Wedgwood family since the early nineteenth century when Josiah I's widow Sarah had made her home there.

The directors would free themselves once and for all from the restraints of Etruria, but at the same time could claim they were recreating Josiah I's original vision of a model factory and village set in sylvan surroundings. The project would enhance Wedgwood's claim to be distinct from and superior to its rivals in the Potteries, and once more make its works and surrounding housing a place of pilgrimage for all those with an interest in what the future could and should look like. The project was made public in May 1936, towards the end of the exhibition at the Grafton Galleries. In his press release Josiah V acknowledged that the tradition of Wedgwood had been built up at Etruria, but argued that 'the Wedgwood tradition prescribes a duty to the future as well as to the past generations; and the new venture is being launched with confidence on a rising tide.' The local press responded enthusiastically to the announcement: '...the most original and courageous adventure which has been witnessed in our time' proclaimed the Evening Sentinel. 'If old Josiah had not hitched his wagon to a star, he would not have attained a reputation that is still at the peak of industrialism wedded to scientific artistry. History may well be repeated.'

" pp. 37-40 |

|

Related pages Wedgwood Etruria Works in 1926 Details of Wedgwood's five works also see.. Advert

of the Week

|